- Home

- C. S. Richardson

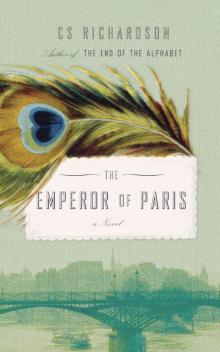

The Emperor of Paris

The Emperor of Paris Read online

COPYRIGHT © 2012 DRAVOT & CARNEHAN, INC.

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication, reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system without the prior written consent of the publisher—or in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, license from the Canadian Copyright Licensing agency—is an infringement of the copyright law.

Doubleday Canada and colophon are registered trademarks

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Richardson, C. S. (Charles Scott), 1955-

The emperor of Paris / C.S. Richardson.

eISBN: 978-0-385-67091-3

I. Title.

PS8635.I325E46 2012 C813’.6 C2011-908531-3

The Emperor of Paris is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Cover design: Kelly Hill

Images: SuperStock/Getty Images, BOISVIEUX Christophe/hemis.fr/Getty Images, Shutterstock.com, Clipart.com

Published in Canada by Doubleday Canada,

a division of Random House of Canada Limited

Visit Random House of Canada Limited’s website: www.randomhouse.ca

v3.1

For Hannah and Alexander

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

First Page

Acknowledgements

The observer is a prince enjoying his incognito wherever he goes. The lover of life makes the whole world into his family, just as the lover of the fair sex creates his from all the lovely women he has found, from those that could not be found, and those who are impossible to find, just as the picture-lover lives in an enchanted world of dreams painted on canvas.

CHARLES BAUDELAIRE,

The Painter of Modern Life, 1863

For the gossips of the bakery it becomes irresistible: the wisps of smoke up their noses, the voices under their windows, the footfalls of curiosity on the move. They are the first to arrive, these busybodies, shading their meddlesome eyes and comparing their hare-brained theories.

Mark this day, someone says. We are witnessing the devil’s work. Only Satan would burn a library.

It is providence, comes a retort. God’s design unveiled to us mortals.

Either way, says a third, it is a cruel deity. A cruel one indeed, dooming a good man to such a horrible fate.

The bakery’s more level-headed regulars appear. Some to stand rooted to the cobbles in disbelief, others to pace back and forth, frantic now to do anything that might help their bread man. An old fellow elbows through the mob and pulls at the bakery’s blue doors. The locks hold firm, his thick spectacles knocked askew with the effort. Three or four boys scatter in search of buckets; a fifth runs off to call the fire brigade. An elderly woman shouts the address after him.

Heads are scratched and hands are wrung. In the summer heat handkerchiefs are pulled from pockets and sleeves; foreheads wiped, eyes dabbed, mouths covered. A bout of coughing, then someone asks if anyone has seen the baker.

Out wandering, I should think. Sunday after all.

A fortunate day then, and all the better that our man isn’t here. Imagine watching your life going up in flames. Luckier still he isn’t cinders himself.

And where will all this luck be, I ask you, when he arrives home to nothing? After all his collecting, all those armloads of books? It will break the man’s heart.

A cruel one indeed.

The crowd becomes a small fidgeting sea in front of the bakery, each face turned to a sky the colour of pearls. They watch in silence, holding their children close, praying the brigade is not delayed in traffic. Above them the baker’s apartment disappears.

Smouldering flakes begin to blossom in the heavy air, sliding over slumped shoulders, resting for a moment on shoe tops, dying tiny shrivelled deaths in the street. There are glimpses here and there: a sentence, a phrase, a doomed word drifts by. Among the singed white bits are shards of red leathers and frayed blue cloths, the curled and blackened edges of marbled papers, melted strands of silk ribbon, everything spinning slowly to the ground.

On a July morning in the eighth district of Paris, it begins to snow.

In his time the baker’s father had been a celebrated man, though he held no official title. A sign had never hung on the bakery’s doors: BEHOLD EMILE NOTRE-DAME, THINNEST BAKER IN ALL PARIS! Nor had the thought occurred to him to take advantage by placing a notice in the shop window: AND YET HOW STOUT HIS BREADS!

This matter of thinness was the source of endless debate among the gossips queuing for their daily loaves. Some claimed that Monsieur might as well be invisible. With those legs our dear Emile is more than worthy of the honour. Others were certain that among the countless bakers in the city there must be scrawnier candidates. Someone would then suggest that it was not Monsieur’s stature that had made him worthy. Our man is the very model of service, they would say, to his craft and to us. He rises at ungodly hours, makes us good breads in bad weathers, and hands them over with a smile and a story. I could not care less if the fellow were made of twigs.

In the end all agreed it was a marvel—considering the temptations of butters and yeasts and eggs—that any baker anywhere in France might be as slender.

There was never a discussion regarding the size of the baker’s wife. A woman of Italian descent and feverish religion, Madame Immacolata Notre-Dame was in her other aspects generously round. Only her head was small: a gracious sphere covered with black hair drawn to the nape of her neck, her high-collared blouses making her head appear all the smaller. No one addressed her as Immacolata. To all she was simply, piously, Madame; and her Emile was their Monsieur.

The bakery occupied the ground floor of a narrow flatiron building known throughout the neighbourhood as the cake-slice. As far back as anyone could remember the letters above its windows, in their carved wooden flourishes, had spelled out:

BOULA GERIE NOTRE-DAME

the N having long since vanished.

All who visited the bakery agreed the signage was as charming as the squeezed triangle of building that housed the bakery and the thin and thick of its husband-and-wife proprietors. Yet there were demands that Monsieur make repairs. The more excitable gossips insisted that tourists might loiter, having made a wrong turn somewhere and found themselves unable to decipher boula and gerie. You will have these poor souls, monsieur, fumbling for a guess that the broken word means cathedral. Which will only make them anxious as they wonder if they are in the right district at all. Then there will be the emptying of luggage in search of phrase books and maps. And then, monsieur, you will have the unthinkable: underclothes and stockings and goodness knows what else thrown all over the street.

To calm these worries, Monsieur would concoct a story concerning the N’s disappearance. He might begin by suggesting that Napoleon himself had taken it. The little general would spring to life in the figure of Monsieur: climbing a wobbling ladder, straining to reach the prized letter, prying stubborn nailheads with his fingers. With each telling the location of the missing consonant changed. It once turned up in Les Invalides, glued with wallpaper paste to the lid of the great man’s tomb. Monsieur leaped from the last invisible rung and took a deep bow.

You are welcome to retrieve it, my friends.

The bakery’s location in a building named for a pastry confection was an irony lost on no one. For centuries there had been an order to the world, a natur

al division of gastronomic labours. Bakers worked their dough, pastry men fussed with their marzipan. Each kept to his own, begrudging enough if he found himself walking past the other’s shop. To feed your family, you were off to the boulangerie. Weakness for a macaron meant a trip to the patisserie and be quick about it. It was a sensible order: everyone knew to visit a fruit seller when looking for a squash was foolishness; dogs and cats in the same litter meant the end of civilization.

Yet these were modern times, the gossips were quick to remind. We must change as the world does, monsieur.

All too easily for Monsieur’s liking. Bread was the stuff of life, for him the stuff of generations: the Notre-Dames had been bakers as far back as there had been Notre-Dames. We have fed kings and washwomen, he would boast. Our breads have soothed teething babies and started revolutions. I ask you: would you sop up your grandmother’s cassoulet with a handful of apricot jam? I should hope not.

No. Monsieur would not betray a guild older than the Pyramids by fooling with custards and icings. Others might offer their éclairs alongside their country rolls—heaven forbid in the same display case—but such fraternity was not for him. You can stuff me with mousse, he would grumble, before I start ladling meringue into a pie and serve up a month’s worth of indigestion for my trouble.

Each customer remained just as loyal to this creed, though on occasion, should Monsieur take a break from the ovens and join his wife upstairs, a quiet comment about raspberry tarts might slip out of a gossip’s mouth.

The walls of the bakery were decorated with allegories: a woman with blushing cheeks held a bouquet of wheat sheaves to her bosom; a laughing baker snorted plumes of aroma from a glowing oven; winged infants hoisted trays of pains au chocolat, delivering breakfast to the gods. A glass case stretched the length of the shop, displayed ranks of braided loaves, croissants nestled like lovers, curve within curve, boules scored with the initials N-D, baguettes in two lengths. Next to the case sat the till, an iron beast requiring a well-swung fist to open the drawer. Wicker baskets were everywhere, in chronic danger of being knocked over, and overflowing with varieties of sourdough and rye, wheat rolls with sweet hidden raisins, and Monsieur’s gently herbed brioche.

Above the door to the cellar and its ovens hung a calendar advertising a peerless and heavenly beer. The calendar featured a portrait of the Virgin Herself, in shades of pink and purple, her eyeballs spinning in ecstasy, beams of orange light bursting from her head. A golden bottle, sweating in the holy warmth, hovered in the clouds above her.

With the day’s last customer served and gone, Monsieur and Madame would climb the stairs to their apartment in the top of the cake-slice. Morning after dark morning, down to fire the ovens, polish the marble, upright the baskets. Evening after evening, up to home and bed.

The Notre-Dame household was solid underfoot but slightly out of level, a boat nestled at low tide. The lounge and kitchen were one room, furnished with a pair of arm-worn chairs. The dining table had come from a café near the cake-slice, a wedding gift from the proprietor. The bathroom floor sloped its own way into a bedroom where Monsieur would cheerfully move the bed should Madame wish to open the armoire drawer. The attic, reached by a circular staircase that rose inexplicably from the centre of the main room, was a space of rough-hewn beams and mouse-hole corners. If Monsieur leaned out the attic window at a particular angle and shooed away the ever-present gathering of pigeons, he might enjoy a view of the chimney pipes of the district.

Honoré, saint of bakers, stared from prayer cards tacked throughout the apartment. An Italian bible, swollen with strips of paper marking Madame’s preferred verses, was the extent of the Notre-Dame library.

Someone new to the Boulangerie Notre-Dame, standing at the distant end of the morning queue, could enjoy a few distractions till their turn came. Having finally stepped inside, they might admire the bakery’s painted tiles. Or watch the stock of baguettes dwindle ahead of them and worry whether there would be any left when they reached the counter. Or turn their attention to Monsieur and Madame bustling behind the display case. An unlikely pair, the newcomer might wonder, tapping the shoulder next in line and asking how this curiously thin baker and his hefty missus had met. Heads would turn, throats would clear, and the hive of the bakery would come to a halt.

A gossip would say it was strawberry. Another would reply that no, it was raspberry.

As you wish, but I am sure it happened near the river.

In the park, you mean.

Monsieur might slide his arm around Madame’s waist. As I recall we were on the boulevard, he would say.

Well then, Monsieur, it was most certainly a Saturday evening.

Sunday afternoon, Madame would reply, offering a hint of a smile as she spoke, and leaning her head against her husband’s shoulder. The debaters would pay no attention as they circled the newcomer.

You must visualize our baker here, strolling along on his day of rest, his head—

in the clouds as usual, conjuring another story when—

he passes a pastry shop and—

averts his eyes as any proper baker would and—

fails to notice the young beauty emerging from the shop.

Madame would look at her husband. I was eating a tart, wasn’t I?

Monsieur would kiss his wife’s cheek. A treat, he would say. After mass.

There would be the inevitable collision: Monsieur ending up in the gutter, Madame with most of the tart smeared across her face. He leaped to his feet, ready for a yelling match, and turned to meet his foe. There she stood adjusting her shawl, cleaning custard from her dress, blushing and cursing a streak in Italian. She was the most beautiful creature he had ever seen. He smoothed his hair and rummaged through his pockets for a handkerchief. Once he had found it, he paused as she nodded her permission. He wiped a dribble of raspberry ganache from the corner of her mouth. She never stopped staring into his shining grey eyes.

So there it is, someone would conclude. I knew it was raspberry.

The important thing, Monsieur would add, was that it was red.

On that dessert Emile and Immacolata built their life together, though none who knew them were bold enough to remark that such happiness had begun, of all places, outside a pastry shop.

There were the Sunday afternoons in a small café near the Boulangerie Notre-Dame: the same outside table no matter the season, her mother chaperoning a few tables away. Emile would arrive with a copy of the day’s illustrated newspaper tucked under his arm, present the front page with a flourish and weave a tale concerning its illustration. Immacolata would roll her eyes or gasp at the proper moments, not caring that her handsome baker never began his stories by reading the headline.

A front page once featured the unveiling of an enormous marble statue in a far-off museum. Emile spoke of the marble in his own bakery, explaining in a deep voice and with many a dramatic pause that its slabs and tiles had travelled across a sea—teeming with sharks and mermaids, he said—all the way from the quarries of Sicily.

But there is no marble in Sicily, Immacolata said. They have a volcano. There they mould their statues out of molten lava.

But I am sure my marble came from Italy. Certain of it—by boat—across the sea—teeming—

Then your marble began its journey in Tuscany. Like me.

And the sharks—the mermaids?

Immacolata glanced at her mother a few tables away, then placed her hand on Emile’s.

Still swimming as far as I know. I was only little, but I remember watching them through the railing as we sailed away.

——

The spring of 1901 saw Emile and Immacolata married in an alcove chapel of the Church of Saint-Augustin. There followed a small celebration in the bakery. Emile baked the choux buns for the pièce montée himself, admitting to no one that a week earlier—under cover of a late-night stroll—he had consorted with a pastry man in the ninth to produce the cream filling for the buns.

A few

customers had arranged for a duo of cello and violin. Naturally the gossips were first in the queue for a dance with the bride.

On Sunday mornings Madame would drape a shawl over her head, touch the palm of her hand to the nearest Honoré and set off to church. In leaner years she might have been seen shuffling to mass on her knees, and once, as joyful as a martyr, she likewise made the pilgrimage to Chartres by scuffing up and down the aisle on the train from Montparnasse station. Through each mass she prayed to Gabriel, hands clenched, knuckles white, begging for the gift of children.

When his wife had left for services, Monsieur would dress in his one black suit, step out of his clogs and into his Sunday shoes, comb his unruly hair, button his only collar and descend to the bakery. After polishing the counter with his sleeve, Monsieur would step outside, inhale a morning free of flour dust, and place his bony bottom on the curb. Only then did he lean his back against the bakery’s blue doors and scrutinize the pictures in his illustrated newspaper.

On an afternoon in December of 1907, with a north wind stabbing at the bakery windows, Madame received an answer to her prayers. As though a lover’s breath had wafted across the nape of her neck. Standing behind the counter, she held a hand against her cheek, then crossed herself. She caught her fingers in the closing drawer of the till.

Next? she said, perhaps too loudly.

Through the following summer Madame seemed to double in size. The morning of the eighth of August found her in hard labour in the cellar of the bakery, splayed on the same table where, were it any other Saturday, Monsieur should have been scoring his second lot of baguettes. In spite of the early hour, the day promised to be the hottest of the summer.

Ovens at full heat, rising loaves overflowing their pans, Madame’s ankles balanced on Monsieur’s shoulders, customers filling the shop upstairs and fretting about whether anyone had gone to fetch a doctor, the gossips among them suggesting hot water and cold towels and opening or closing as many windows as possible, all combined to make circumstances in the bakery more uncomfortable than anyone could have imagined.

The Emperor of Paris

The Emperor of Paris